As the field of bandit evolves, there are tons of papers showing up every year. Rather than reading them one by one, this post aims to give the most general intuition on how to think about this type of problem, and three most famous benchmark algorithms.

We go back to the lottery problem described in the last post. The reason we need to think about strategies is that we are uncertain which machine gives the best winning rate. If we know which one is the best, we would just play that one and not worrying about best-arm identification and regret minimization and so forth. Uncertainty is a key issue we would like to overcome. In some sense, we are making inference about the underlying unknown characteristics of the machine by our observation. How would we measure “uncertainty”? In the lottery example, this is measured by the variance. If we let $p_1$, $p_2$, $p_3$ be the winning probability of machine 1, 2, and 3, then the variance measures how large each observation deviates from those true probabilities. In order to find out the best machine, we need to minimize the uncertainty as quick as possible.

How to minimize uncertainty? On one hand, if you play one machine more and more times, you will get a better sense of how good the machine is. On the other hand, if you play more and more machines, you will have a better chance of playing the best machine. Therefore, there is a natural tradeoff between playing more machines and playing one machine more times. This tradeoff is called the balance between exploration and exploitation. All bandit algorithms are trying to find the best balance.

In bandit literature, there are three most famous benchmark algorithms for this purpose. Two for regret minimization: UCB and Thompson sampling, and one for best-arm identification: elimination. In what follows, we will introduce UCB and elimination algorithms and the intuition behind them.

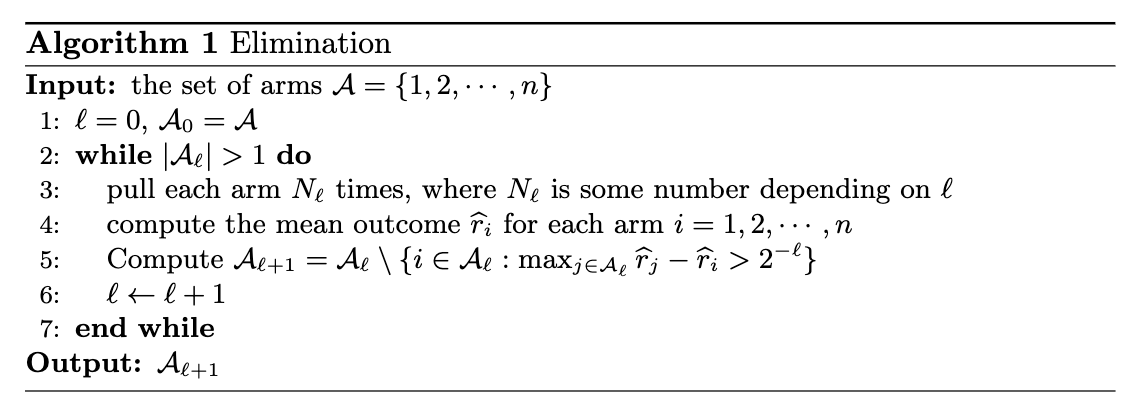

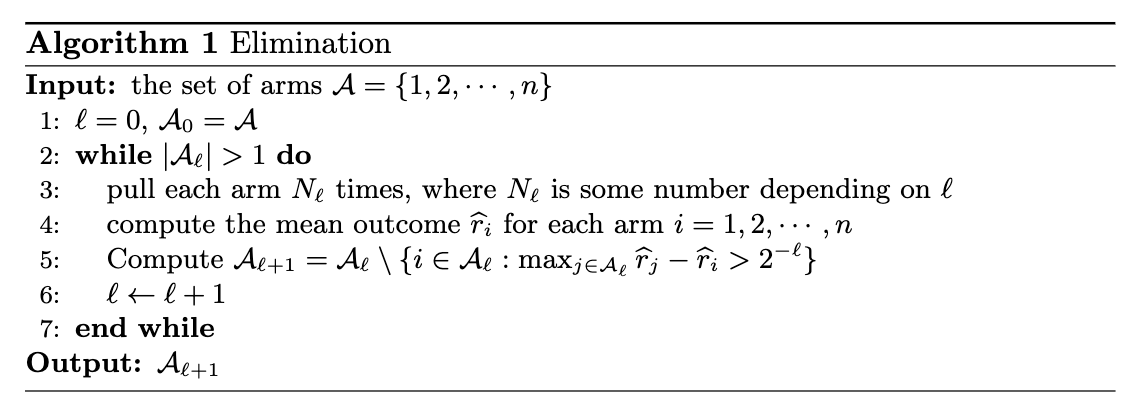

The elimination algorithm is used for finding the best arm, or in the lottery example, finding the best machine. The intuition behind this algorithm is that when you play each machine enough times, the uncertainty decreases. You will have an idea that certain machines is probably not going to be the best, since they perform so badly in these times you play them. Therefore, you only need to keep playing those machines which could still be good. More formally, this algorithm proceeds in rounds. In round $\ell$, it eliminates all arms whose gap to the best arm is greater than $2^{\ell}$. The framework of the algorithm is as follows:

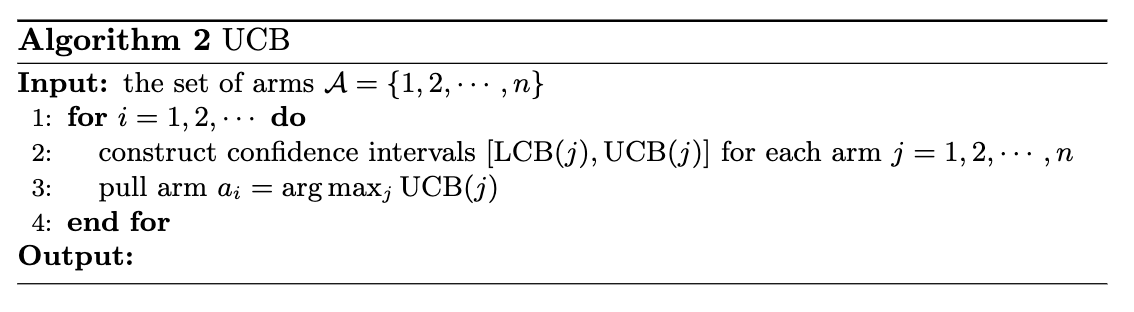

The UCB algorithm is used for minimizing the regret, in other words, lose the least amount of money in 100 runs. The principle behind this is “optimism in the face of uncertainty”. In the lottery example, when you play a machine for some times, you can construct a confidence interval for the true winning probability. The UCB algorithm, in each round, plays the arm whose upper confidence bound is the largest. In other words, in each round, it plays the machine who could potentially has the largest winning probability, given the current information. The framework of the algorithm is as follows: